Andrea Slavik Interview

As an interdisciplinary artist and educator, Slavik seeks to challenge popular ideological practices and forms of representation active in western culture. She completed graduate studies at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and has exhibited in North America and Europe. Current topics of engagement for works in progress include: speculative fiction, nuclear semiotics, and queering/hacking RPG frameworks. This interview was conducted by CAPE Program Coordinator Brandon Phouybanhdyt.

BP: What aspects of experimental film or experimental video art affords teachers to open up their curriculum and what makes it a good medium to work with in class?

AS: Much historical and contemporary experimental film and video, both representational and non-representational, embodies a formalist or structuralist approach where artists experiment with the materiality of the medium (time, light, frame, movement, sound), meaning that they creatively explore the basic elements and mechanisms of film and video.

This way of working began as a response to break free from narrative filmmaking, a genre that was and still is heavily informed and influenced by theatre and commercialism.

Painters, sculptors, writers etc., throughout the late 19th century to the mid 20th century were defining modernity by breaking down forms, experimenting with reflexivity and moving towards abstraction. Filmmakers and later video artists also began to see the moving image as a medium in its own right and were thinking of new and avant-garde ways of using it, where absent are the elements from other art forms normally present in films like acting, plots etc.

For many classroom projects, experimental video is a great starting point for beginners because you begin with really looking at the basics of your medium and participants can take it as far as they are able to or want to. Projects like this I find are accessible by most ages and abilities.

For instance, in our geometry math class at Vaughn, the teacher and I decided to facilitate an animation project where students used an iPad, digital pencil, and an inexpensive animation app to learn about two-dimensional and three-dimensional shapes.

The student and teacher do not have to be familiar with drawing representational objects and they can immediately begin to explore the infinite and dynamic ways one can draw and animate lines, shapes, colors and textures to convey mood and energy. Shapes don’t have to be static and boring and abstraction can be a form of expression.

For a frame of reference, we as a class looked at the relationship between avant-garde or modernist painting and avant-garde or experimental film. We discussed basic color theory and hard-edged geometric abstraction in color field painting and film/video. We learned about abstract modernist painting in general, which also broke down the basic elements of the medium (canvas, paint, color, texture, shape) to explore the possibilities of non-representational images on a two-dimensional surface. Most of the works we looked at and discussed were from the early 20th century up to the 1970’s with some contemporary pieces in the mix.

We also looked at how abstract painters and filmmakers were influenced by and used lyric-less music that can also be considered abstract like jazz and electronically produced sound. I felt like I was taking a chance and participants would find this kind of old school stuff unengaging but they were really into it and in the end, the project was well received by the school community and gallery audiences!

What’s also great about using short-form experimental moving image formats in the classroom is all the options of sub-genres it affords the student: poetic lyricism, diaristic filmmaking, found footage filmmaking, experimental documentary, city symphony, stop motion, animation, etc. You can incorporate just about any academic subject like math, science, social studies, creative writing, and history in a moving image work, perhaps even more so than other mediums. Creating a conventional narrative film with plots, acting, etc. requires a pretty rigid process and equipment that most schools do not have.

Throughout the years, my students made all kinds of videos that engaged with various subjects and topics like migration, anger and anti-black racism, bullying, student-teacher relations, social justice, memory, identity, history, social studies, geometry, states of matter, arithmetic.

BP: How does experimental video or movie image expand students’, teachers’, non-artists’, conception of technology?

AS: One of my goals is to encourage students, and even teachers to use personal devices like tablets and smartphones to produce meaningful cultural products rather than just consume cultural products. Accessible and versatile consumer technology like the iPad is particularly conducive for making time-based and experimental moving image work in the context of a classroom project. In the past, you would need several specialized and expensive pieces of “prosumer” equipment to do all the things you can do on one device now. Also, one of the hallmarks of experimental or avant-garde moving image work is the use of new technologies to create new forms. For example, in 1965, video art pioneer, Nam June Paik purchased the first consumer video camera called the Sony Portapak in the US.

Here are some things that students can do on one device:

-

take photos, videos and sound recordings

-

edit and render photos, videos and sound recordings

-

generate sounds and create a music track

-

video map architecture

-

produce stop motion animations

-

produce hand drawn digital animations

-

produce special effects with green screen and data bending apps

-

produce an animated text-based video for an installation a la Jenny Holtzer

-

share and promote work

-

research related information online and make notes

-

use as a playback device for performances, presentations and installations

Animation in general is produced by creating each individual frame. It’s kind of a bonus that students learn about the underlying mechanics of the medium they are working with while creating their projects. Students begin to understand the notion that moving images are constructed illusions created through a series of frames and activated by a theoretical phenomenon known as the persistence of vision. This is where we segue into a class discussion about critical issues like representation in the media.

That being said, what I would like to see is access to professional level equipment and expertise at public schools, especially for high school level students who want to compete with privileged private school students to earn scholarships and study media in post-secondary. Having students use iPads to film and edit is not ergonomically ideal, limits their potential for learning and applying professional media production and post-production skills, and for the most part, doesn’t adequately prepare students for rigorous post-secondary media studies programs. High school students could really benefit from accessing gear like microphones and boom poles, HD cameras with manual settings, external video monitors for filming and editing, fluid head tripods, dollies, light kits with diffusing material and colored gels, and desktop computers with professional editing programs like Final Cut Pro. As useful as iPads or tablets are for some school projects, age groups, and beginning level students, supplying schools with just tablets for media projects and other educational purposes is a cheap, roundabout, neoliberal alternative to providing schools with the tools and resources many students actually need to get a leg up and thrive.

BP: What is digital media and its relation to experimental video/filmmaking? How does experimental video/digital media transform perceptions of time and space?

AS: Those are big questions! I would recommend reading the following:

Roundtable on Experimental Digital Cinema, MIT Press Journals, 2011.

The Emergence of Cinematic Time, Mary Anne Doane, Harvard University Press, 2002.

For the second part of the question, I’ll give an example of a video one of my students made where she skillfully experimented with spatiotemporality. The work is an experimental diaristic piece with elements of lyricism and was exhibited at the annual Chicago Art Fair at the Merchandise Mart.

Beautifully weaving together archival footage and sound, newly filmed footage, typography, and lyric-less music, the artist takes us on an autobiographical journey to another time and space in her life, where she poetically processes, articulates and expresses her feelings and thoughts on personal loss, nostalgia, and memory.

There are powerful moments where the viewer is simultaneously immersed in the artists past and present. In one instance, she layers archival footage of her little brother playing in the backyard of her family’s old house over top of new footage of the same empty backyard where her family no longer lives. The artist had the gumption to ask the new homeowners to film in their backyard and they obliged. Here, space is occupied by feelings and is not just a physical location; it’s an emotional space.

Another great example of how the artist experimented with time and space/place is when she filmed a slow tracking shot of a row of houses in her family’s old neighborhood which was then superimposed with text that narrated her memories of the area such as “My brother and I used to ride our bikes here.”

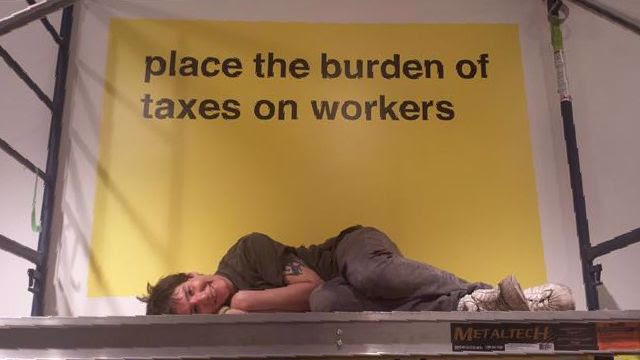

The image above comes from a project by students at Vaughn Occupational High School, where teaching partners Dara Bayliss and Andrea Slavik used animation and stop-motion to illustrate math and technology concepts. Students used geometric shapes to create short animations on iPads and geometric paper cutouts and blocks to create stop-motion videos. Bayliss and Slavik note that the project allowed students to show-case a different set of skills then they usually display in math class. See full CAPE Network Forum post and video here.